Richard Dawkins Relates A Story About Carl Gustav Jung That Never Happened.

“Dawkins and Hitchens miss two important points. First, their critics are not only talking about their scholarly limitations but about their errors, errors that a more informed or careful critic wouldn’t make…”.

Curtis White, The Science Delusion: Asking the Big Questions in a Culture of Easy Answers (with new afterward; Brooklyn, London: Melville House, 2014), 35.

As you surmise, Dawkins has conflated the two episodes."—Sonu Shamdasani

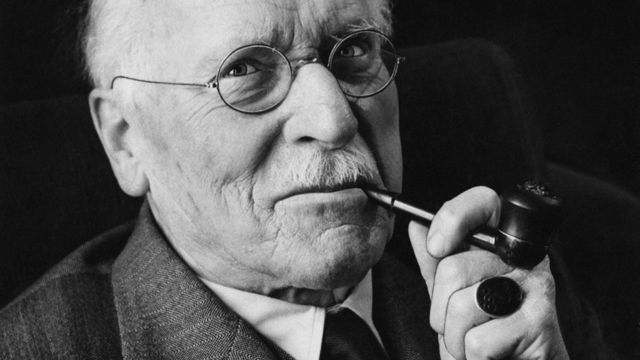

So, there it was. An email from one of the most distinguished

Jungian scholars in the world confirming what I felt sure I already knew, namely, that in

an attempt to make an appeal to an incident in the life of Psychologist Carl

Gustav Jung, Richard Dawkins had somehow conflated two real incidents that did happen into a single one that did not happened. This is not of course the

only place Dawkins makes such flubs in The

God Delusion (see, e.g.,

Richard Dawkins Bemoans/Models

Biblical/Biblical Illiteracy). Both cases speak to Atheist writer

Curtis White's comment on how Dawkins' "critics are not only talking

about...scholarly limitations but about...errors that a more informed or

careful critic wouldn’t make."

Anyway here is what Dawkins wrote:

"It is

in the nature of faith that one is capable, like Jung, of holding a belief

without adequate reason to do so (Jung also believed that particular books on

his shelf spontaneously exploded with a loud bang)." (The God Delusion [Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin,

2009], 51).

But Dawkins is confused. Nothing like that ever happened. Rather Dawkins clumsily conflated two different incidences. The first is the famous 1898 incident in which a knife inexplicably

exploded into four parts while locked in a sideboard cupboard and the second the

equally famous 1909 incident when Jung was visiting Freud in Vienna and both

were startled by a loud report suddenly coming from Freud's bookcase.

Immediately after that first report, Jung predicted a second would occur,

which duly happened. Both incidents are frequently referred to in writings by

and about Jung. Let us turn then to the accounts of these two incidents.

The Exploding Knife

I feature the account in Jung’s own hand in a letter he wrote in

1934 to J. B. Rhine:

The knife was

in a basket beside a loaf of bread and the basket was in a locked drawer of a

sideboard. My aged mother was sitting at a distance of about 3 meters near the

window. I myself was outside the house in the garden and the servant was in the

kitchen which is on the same floor. Nobody else was present in the house at

that time. Suddenly the knife exploded inside the sideboard with the sound of

an exploding pistol. First the phenomenon seemed to be quite inexplicable until

we found that the knife had exploded into four parts and was still lying

scattered inside the basket. No traces of tearing or cutting were found on the

sides of the basket nor in the loaf of bread, so that the explosive force

apparently did not exceed that amount of energy which was just needed to break

the knife and was completely exhausted with the breaking itself.

(Jung to J.

B. Rhine, November 27, 1934, in C.

G. Jung Letters I: 1906-1960 [Bollingen

Series XCV:1; ed. Gerhard Adler & Aniela Jaffé; trans. R. F. C. Hull;

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973], 181).

From: Aniela Jaffé, C. G.

Jung: Word and Image (Bollingen Series XCVII: Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press, 1979), 32.

The same story is also related in Jung’s memoir Memories,

Dreams, Reflections (edited

by Aniela Jaffé) with some additional details including that:

The knife had

been used shortly before, at four-o’clock tea, and afterward put away. Since

then no one had gone to the sideboard. The next day I took the shattered knife

to one of the best cutlers in the town. He examined the fractures with a

magnifying glass, and shook his head. “This knife is perfectly sound,” he said.

“There is no fault in the steel. Someone must have deliberately broken it piece

by piece. It could be done, for instance, by sticking the blade into the crack

of the drawer and breaking off a piece at a time. Or else it might have been

dropped on stone from a great height. But good steel can’t explode. Someone has

been pulling your leg.” I have carefully kept the pieces of the knife to this

day. My mother and my sister had been in the room when the sudden report made

them jump. (Carl Jung, Memories,

Dreams, Reflections (rev.

ed.; recorded & ed. Aniela Jaffé; trans. Richard & Clara Winston; New

York: Vintage Books, 1973), 106.

(We notice a discrepancy: in the first telling Jung lists his

mother and a servant as being the only ones present in the house and in the latter his mother

and sister).

Jung kept the broken knife and showed it to people,

including, for example, E. A. Bennet, who reports seeing it some 60 years after

the alleged event (see Meetings

with Jung: Conversations Recorded During the Years 1946-1961 by E. A. Bennet [Zürich: Daimon,

1985], 86). When Jung died the shattered knife remained in the possession of his

family (according to Aniela Jaffé, From

the Life and Work of C.G. Jung: Jung’s Last Years and Other Essays [trans. R. F. C. Hull & Murray

Stein; Zürich: Daimon, 1989], 3).

The Loud Report in Freud's

Bookcase

Here is the account of the incident from Memories, Dreams, Reflections:

I [Carl Jung]

had a curious sensation. It was as if my diaphragm were made of iron and were

becoming red-hot—a glowing vault. And at that moment there was such a loud

report in the bookcase, which stood right next to us, that we both started up

in alarm, fearing the thing was going to topple over on us. I said to Freud:

“There, that is an example of a so-called catalytic exteriorization

phenomenon.” “Oh come,” he exclaimed. “That is sheer bosh.” “It is not,” I

replied. “You are mistaken, Herr Professor. And to prove my point I now predict

that in a moment there will be another such loud report!” Sure enough, no

sooner had I said the words than the same detonation went off in the bookcase.

To this day I do not know what gave me this certainty. (pp. 155-56)

Freud himself refers to the incident in an April 16, 1909, letter

to Jung, offering his own solution as to the possible origin of the seeming

incident of “poltergeist phenomena”:

At first I

was inclined to ascribe some meaning to it if the noise we heard so frequently

when you were here were never heard again after your departure. But since then

it has happened over and over again, yet never in connection with my thoughts

and never when I was considering you or your special problem.

Freud's letter is included as an appendix to Memories, Dreams, Reflections (p. 361 / see also The Freud/Jung Letters [Bollingen Series XCIV; ed. William

McGuire; trans. Ralph Manheim & R. F. C. Hull; Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press, 1974], 218 [139F]).

Conclusion

What does Dawkins’ conflation of these two famous stories fro the life of Jung mean?

Well, for one thing, it suggests that Dawkins does not regard

getting all the facts and/or getting them right to be a prerequisite for intelligent

discourse or even for arrival at a definitive opinion. It reveals he is ready to write,

to argue, to pontificate, to publish, to attack the views of others, on no better basis than sketchy rumors or vague

recollections of things he heard or read somewhere at some time or other, which he believed, to quote Dawkins himself, "without adequate reason to do so." This is scarcely

a quality normally associated with true men of Science.

It means further that Dawkins has not embraced or internalized the value the

great early Christian theologian Augustine reflected when he once scolded himself for

being “rash and impious,” because he "had spoken in condemnation of things

which [he] ought to have taken the trouble to find out about" (Confessions

6:3). Apparently for Dawkins speaking in condemnation of things he ought to

have taken the trouble to find out about is simply the way he operates, at least to the extent that the example under discussion is representative.

One certainly doesn't have to credit Jung's experiences or his

interpretations of them to appreciate the problem here. In making such factual

blunders Dawkins presents himself to his reading public as a careless, sloppy, impatient, thinker, and as such they can only expect that relevant

questions obvious to others are going to prove elusive to him. We can see this

in the present case when we ask how it was that Carl Jung, if really the ridiculous religious clown Dawkins make him out to be, came to count very intelligent people, including Nobel Prize winning scientists Wolfgang

Pauli and Tadeusz Reichstein, among his friends and admirers?

Comments

Post a Comment