On the Positive Impact of Learning You Can't Trust the Dictionary

|

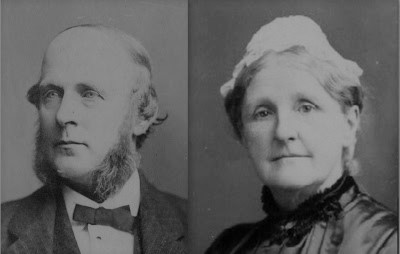

| Robert Pearsall Smith and Hannah Whitall Smith |

The details have become become somewhat indistinct in my memory, but it happened while I was working on my doctoral dissertation and was trying to interpret a letter, written around 1870, in which the famous Christian Higher-Life writer Hannah Whitall Smith, wrote a letter to her husband, Robert Pearsall Smith, who was in a sanitarium. The letter made reference to the word PETTING in connection with Robert and his nurses. One interpreter of the letter presumed the reference alluded to hanky panky, a thing Robert indisputably engaged in later in his career. The ones doing the PETTING in the letter were the nurses not Robert.

However, reading the letter I could not discern anything in Hannah's tone except friendly wifely concern, and I wondered whether the term PETTING could have had connotations that were entirely innocent when used in reference to the behavior of nurses in 1870. So I hoisted my massive Random House Dictionary off the shelf and had a look at its etymology (word history) for PETTING. The date given when PETTING first took on sexual connotations ("amorous caressing and kissing") was 1870-1875, i.e., roughly the date of the letter. I checked other sources and could not find evidence of PETTING being used with sexual connotations that early.

I noticed that the name of the dictionary's editor was Stuart Berg Flexner. I knew that Flexner was a name associated with the extended family of the Pearsall Smiths. So I wondered whether the letter I was looking at might have somehow provided the actual source for the date in the dictionary's etymological reference, but if is was, I felt sure they'd misread the intent of the letter.

I put in a call to Flexner and left a message on his answering machine outlining my question and suspicion. Flexner checked it out and called me back informing me that the dictionary's etymology had indeed been mistaken based on a misreading of the word files of the Oxford English Dictionary.

To me this was a watershed experience, since I like most people had always simply assumed that if any reference work could be trusted, it was going to be the dictionary.

I remember an experience early in my life growing up in Northern Idaho. The kids I used to play with at the farm across the street regularly used the word AIN'T, a word I liked well enough but one that had been banned from my mouth by my mother. She had informed me in no uncertain terms that AIN'T wasn't a word.

Naturally I was eager to share this information with my friends across the street. So when we next met for play I informed them:

"AIN'T isn't a word!"

"AIN'T isn't a word!"

"Tis' too" they replied, "It is a word, Why AIN'T is even in the dictionary."

In disbelief, I asserted. "No its not!"

But of course when my mother and I checked the dictionary, there AIN'T was in plain black and white. The offending word was in the dictionary, I was embarrassed at showcasing my ignorance in front of my friends, and my mother's sterling reputation as an infallible source for correct linguistic information became just a little tarnished in my young eyes. Even today the online Merriam-Webster Dictionary for AIN'T includes a usage note addressing the question "Is AIN'T a Word?"

That experience also played a part in my eventually coming to understand that dictionaries don't make up the language they merely chronicle it. They don't create English words or assign them their meanings, they merely report on their ongoing status as tossed along on English speaking tongues through time.

That experience also played a part in my eventually coming to understand that dictionaries don't make up the language they merely chronicle it. They don't create English words or assign them their meanings, they merely report on their ongoing status as tossed along on English speaking tongues through time.

But the problem extends beyond the Random House Dictionary. The same kind of thing can even be found in that distinguished magisterial authority on English words, the highly respected Oxford English Dictionary (see, for example, my comments on that dictionary's entries on LIP-SERVICE and BOO and HOMOPHOBIA).

(on an ironic note, Robert and Hannah's son Logan Pearsall Smith, actually worked on the Oxford English Dictionary).

The idea that even the Oxford English Dictionary might be wrong and must always be fastidiously cross checked, helped me immensely in coming to terms with the provisional nature of all human knowledge and interpretation. Even the question as to when a word was first used in a particular way with a particular meaning is contingent upon whoever was saying so having properly interpreted the text they were citing.

By this I do not mean that I became in any sense, dubious about the possibility of meaning or of getting things right. Rather I became dubious of human assertions about knowing things, about their perpetual posturings and pretensions about having achieved certainty on this, that, or the other.

I'm sorry, but if you haven't traced the evidence all the way to the bottom yourself (or as close to it as it is possible to get), then you're really only parroting the opinions of others, and those others may very well be mistaken. You can't really say you really know. What you can say is that you trust that the person or persons who made the assertion really know(s). But that's not quite the same thing, is it? Laying out the credentials of people, however distinguished, or asserting that they speak with the authoritative voice of "Science" or "Scholarship" (both capitalized) only speaks to their being trusted to know, not to their actually knowing. It amounts really to making an argument from authority or consensus or seeming statistical probability, not from facts or evidence. And against such one can only say, if the Oxford English Dictionary can be wrong, then anyone can.

By this I do not mean that I became in any sense, dubious about the possibility of meaning or of getting things right. Rather I became dubious of human assertions about knowing things, about their perpetual posturings and pretensions about having achieved certainty on this, that, or the other.

I'm sorry, but if you haven't traced the evidence all the way to the bottom yourself (or as close to it as it is possible to get), then you're really only parroting the opinions of others, and those others may very well be mistaken. You can't really say you really know. What you can say is that you trust that the person or persons who made the assertion really know(s). But that's not quite the same thing, is it? Laying out the credentials of people, however distinguished, or asserting that they speak with the authoritative voice of "Science" or "Scholarship" (both capitalized) only speaks to their being trusted to know, not to their actually knowing. It amounts really to making an argument from authority or consensus or seeming statistical probability, not from facts or evidence. And against such one can only say, if the Oxford English Dictionary can be wrong, then anyone can.

As a New Testament Scholar the discovery that dictionaries err has served me well toward keeping my eye out for errors in the standard lexicons in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and so on. The reality is that that they all just provide provisional explanations of words and meanings based on the state of knowledge at the time of their publication and the carefulness or carelessness of the various contributors. With the rise of the internet the importance of keeping this in mind has become particularly acute. This is because of the wide availability of lexicons that are online because they're old and have gone into the public domain, which is the same reason they may well be counted upon be outdated as well.

For one example of this relating to a key argument of current Christian Universalists that is based on an outdated understanding of a Greek word long since corrected in more recent (non-public domain) lexicons, see my Cutting-Edge Obsolescence: Rob Bell’s Reliance on a Long-Discredited Universalist Rendering of Matthew 25:46 in Love Wins.

Comments

Post a Comment