Comments on the Sources of the Theology of the "Sectarian Minister" in the 20th Century LDS (Mormon) Temple Ceremony

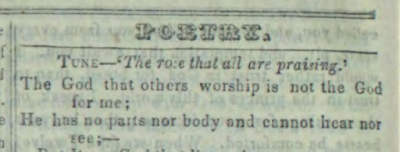

The above hymn is from the early LDS publication Times & Seasons 6.2 (Feb 1, 1845): 799. In studying the apologetic material of a mid-twentieth century LDS apologist some time ago I was struck by the fact that the impression most Mormons of that time had of historic Christianity was not derived from reading historic Christian systematic theologies, talking with members of historic Christian denominations and so on, but rather from a single Mormon source, the parody of Christian theology presented in the preaching of the so-called "Sectarian Minister" in the LDS Temple ritual. That stalk character, who was also represented as a money-grubbing lackey of the devil, was, I believe, finally retired in the 1990s. He was not always a part of the ritual. At an earlier stage several sectarian preachers were present saying the same kinds of things.

In the ritual the "Sectarian Minister" preaches to Father Adam at the request of the devil, who is represented as his enthusiastic supporter. Since the presentation of his beliefs is put forward as an alleged representative of those of Protestant Christianity, it is well to inquire into what the theology, the doctrine of God, expressed in the "Sectarian Minister's" little Temple sermon, is, and where it came from. In any case here is what the minister said:

Sectarian Minister [to Adam]: "I am glad to know that you were calling upon Father. Do you believe in a God who is without body, parts, and passions; who sits on the top of a topless throne; whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere; who fills the universe, and yet is so small that he can dwell in your heart; who is surrounded by myriads of beings who have been saved by grace, not for any act of theirs, but by His good pleasure. Do you believe in this great Being?"

From the descriptive sentences included it is clear that the sermon is meant to sound absurd, even laughable, to the Mormons hearing it. This is especially true of the first three affirmations: "Do you believe in a God who is without body, parts, and passions; who sits on the top of a topless throne; whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere...? Let's look at the some of the sources for each of these phrases in turn.

(1) "Do you believe in a God who is without body, parts, and passions...."

The main source for this statement in the first of the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England: "There is but one living and true God, everlasting, without body, parts, nor passions." A similar affirmation appeared it the historic statement of Reformed (Calvinist) theology known as the Westminster Confession (2.1). Mormons often wrongly suppose that all Christians affirm this. "The whole Christian world," said the late Apostle LeGrand Richards, "believed in a God without body, parts, or passions. That means he had no eyes; he couldn’t see. He had no ears; he couldn’t hear. He had no voice; he couldn’t speak. How could they believe in such a god as that?" (General Conference, April, 1973). The implications Apostle Richards derives from his accusation that "the whole Christian world" believes in a God that can't hear, see, or speak is simply false. But then his intent was not to accurately represent other people's religious views in such a way that they themselves would grant that he was giving an accurate description, but only to bolster the confidence of his LDS hearers. But he is also wrong about the whole Christian world believing in a god without body, parts or passions. The God of the Bible is, if nothing else, represented as a very passionate being. Nevertheless, of the three affirmations made by the Sectarian Minister, this is the only one that has any formal or official standing in the larger Christian community in that it actually does appear in certain historic Christian confessions. Still, as a Christian, who did his doctorate in an Anglican (Church of England) school (Wycliffe College, Toronto), I have to say that I have never been asked in any Christian setting, there or elsewhere, to affirm belief that God is without body, parts, or passions. Nor would I be inclined to affirm it if pressed.

Well before the Mormons got hold of it, the colorful early nineteenth century Methodist preacher Lorenzo Dow (d. 1834) had already stigmatized referring to God’s throne as “topless,” as the sort of thing you would hear in the “a school in the environs of Babylon.” “For how,” Lorenzo asked, “if a throne be topless can one be seated on it?”

[Lorenzo Dow, “A Journey from Babylon to Jerusalem,” in History of Cosmopolite; or The Four Volumes of Lorenzo Dow’s Journal…Also His Polemical Writings…To Which is Added the “Journey of Life,” by Peggy Dow (4th ed.; Washington: OH: Joshua Martin, 1848], 475-76).

But to be fair, that language was poetic and only meant to express the incomprehensible, surpassing greatness of God’s throne, as is seen in a hymn by Isaac Watts that employed it:

Infinite leagues beyond the sky,

The great Eternal reigns alone;

Where neither wings nor soul can fly,

Nor angels climb the topless throne.

Isaac Watts, Hymns and Spiritual Songs in Three Books (Worchester, MA: Isaiah Thomas, 1804), 2:26 (p. 168).

This isn't formal logic, its poetic license, a topless throne is one that is unfathomably high and lifted up, just as a bottomless pit is one that is unfathomably deep. I would be very interested to hear from someone who had traced this topless throne idea back further, but in the meantime why should Christendom as a whole be saddled with the infelicitous line from a writer whose hymns, including such classics as Joy to the World and O God Our Help in Ages Past, appear in both LDS and historic Christian hymnals?

(3) ...whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.... (Latin: "cuius centrum est ubique, circumferentia vero nusquam")

This phrase has been quoted historically by such popular figures as Charles Haddon Spurgeon (“The Sitting of the Refiner,” Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit 27 [1881]: 6) and Alexander Campbell ("The Destiny of Our Country [Aug 3, 1852]," in Popular Lectures and Addresses [Philadelphia, PA: James Challen, 1863], 163). But it is more frequently quoted in sources outside the boundaries of orthodox Christianity. It is often wrongly attributed to the fourth and fifth century writer, St. Augustine of Hippo, as it was, for example, by Carl Gustav Jung in his 1938 Terry Lectures at Yale University (see his Psychology & Religion [New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1938], 66), and Ralph Waldo Emerson in his essay "Circles," (Essays: First Series [New Edition; Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1856], 273). As best as I can tell the statement originates in an anonymous work, the earliest manuscript of which dates from the 12th century, known as the Liber XXIV philosophorum, the Book of the 24 Philosophers. The work is sometimes attributed to sometime Hermes Trismegistus, which would link it with hermetic circles or historic Christian circles colored by hermetic influences. An English translation has been provided by Markus Vinzent, whom I once had the pleasure of sharing in a meal and engaging in a very vigorous discussion over dinner while I was on sabbatical in Austria in 2014. Vinzent's translation can be found here. Finally, this phrase has no official standing among historic Christians at all.

Comments

Post a Comment