Poor Eusebius: Always getting called a liar! Dan Barker's Misapplication of a Passage from Burckhardt

The fourth-century

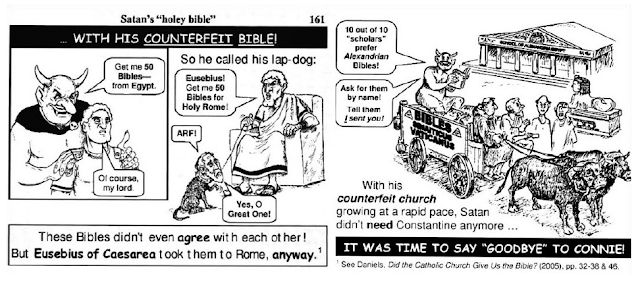

Church father, Eusebius of Caesarea, is forever being given a bum-rap, whether it

be from King-James-Only fundamentalists on the one side or mythicist, historical-Jesus-denying

fundamentalists on the other.[1] The picture I chose to head this post comes

from the former type,[2] but the example I am going

to discuss from the latter type, in a book that makes the following claim:

Eusebius once wrote that it was a

permissible “medicine” for historians to create fictions—prompting historian

Jacob Burckhardt to call Eusebius “the first thoroughly dishonest historian of

antiquity.”[3]

On what authority

the author makes this statement is unclear, since he cites no specific reference

for either of the two claims. Perhaps we

are expected to accept what he says because he is, as the cover of his book proudly

announces, “One of America’s leading Atheists,” a claim, which, if true, doesn’t

speak well for the intellectual vigor of current American Atheism. However, to be fair, the basis for the cover’s

inflated claim may ultimately arise more from the book’s publisher’s hopes of boosting

sales of the book than from any objective comparative criteria for the ranking of

American Atheists.

In any case, as for the author’s first claim, i.e., about how Eusebius, “once wrote that it was a permissible ‘medicine’ for historians to create fictions,” we shall limit our response to a simple, unembroidered denial. In fact, Eusebius never wrote any such thing. Those who wish to pursue this erroneous mythicist commonplace further, will find that Roger Pierce over at www.tertulliain.org has done an excellent job getting to the bottom of it.[4]

Our interest here is

to provide a brief note of perspective regarding the author’s second claim concerning

the 19th century historian Jacob Burckhardt’s characterization of Eusebius

as “the first thoroughly dishonest historian of antiquity.” In fact, Burckhardt did say that, though not, as our author claims, in response to the remark

Eusebius never made about fictional history being good medicine.

Now, as is almost invariably the case for mythicists, our author’s appeal to Burckhardt represents a reliance on outdated scholarship. Such reliances are so typical that one might almost imagine that in order to be a mythicist one must also be allergic to current scholarship.

In Burckhardt’s

case we are dealing with a thesis about Constantine that would scarcely receive

the unqualified endorsement of Constantine scholars today. Burckhardt argued that Constantine was basically

a political animal top to bottom, that his friendly overtures toward the

Christian Church were largely a matter of political expediency, and, in fact,

that “throughout his life Constantine never assumed the guise of or gave himself

out as a Christian but kept his free personal convictions quite unconcealed to

his very last days.”[5] Burckhardt admits that although

he feels sure this is what Constantine was really like, the historical sources fail

to provide him with the evidence he needs to prove it.[6] And, of course, the centerpiece of those sources

were the works of Eusebius, and especially his Life of Constantine, which Burckhardt was reluctantly forced to

rely on all the way through his book. The

long and short of it, then, is that for Burkhardt’s thesis to work, Eusebius needed

to be a liar. Eusebius presented an impediment

to Burckhardt’s thesis, and, as a result, Burckhardt was perhaps a bit too keen

to discredit him. Consequently, although

some of his arguments did in fact touch upon real flaws in Eusebius’s telling

of Constantine’s story, he nevertheless went too far.

To be sure

Eusebius, in his enthusiasm over the favor Constantine showered on the Church, did

tend to undersell Emperor’s faults and oversell his virtues. But that’s always been a common thing for churchmen

to do when trying to stay in the good graces of the seat of power. One only need think, for example, of the lickspittle

first line of the dedication in the original 1611 King James Bible as a

parallel example:

Great and manifold were the blessings (most dreadful Soueraigne) with Almight GOD, the Father of all Mercies, bestowed upon vs the people of ENGLAND, when first he sent your Maiesties Royall person to rule and raigne ouer vs,” etc. etc., ad nauseam, in saecula saeculorum, amen.

As to the question of the sincerity of Constantine’s Christian faith, we face the same sort of ambiguity today when trying to decide whether to believe a particular American President or politician who says they are a Christian. On the one hand, if they behave badly, we may be inclined to count it as a proof positive that their confession is a sham. And certainly Burckhardt made that case in response to Constantine, just as many people today make the case in response to Donald Trump’s asseverations of personal Christian piety. Yet neither Constantine nor Trump acted as wickedly as any number of the “Christian” Kings of England, not least among them being King Henry VIII himself, the man through whom the title “defender of the faith,” first attached itself to the British throne. All this only goes to show that one can never really prove the absence of Christian confession by the presence of bad behavior. So ultimately one can only ask whether a politician claiming to be a Christian actually supported Christian causes, and this Constantine certainly did.

Branding Eusebius

a liar has a similar function as well for King-James-Only defenders who blame

Eusebius for corrupting the Bible (even though he never did) in order to establish

the superiority of the King James over more modern translations that are based upon

older and better manuscripts. So too, in the case of our leading atheist author,

the deployment of Burckhardt’s accusation also serves a purpose in terms of the

argument he is trying to make in the context.

As is typical of mythicists, he

is keen on clearing the deck of any possible early non-Christian witnesses to

the existence of Jesus. One such witness is the late first-century Jewish historian

Josephus, whose Antiquities contains the

following passage:

About this time there lived Jesus, a wise

man, if indeed one ought to call him a

man. For he was one who wrought

surprising feats and was a teacher of such people as accept the truth

gladly. He won over many Jews and many

of the Greeks. He was the Messiah. When

Pilate, upon hearing him accused by men of the highest standing amongst us, had

condemned him to be crucified, those who had in the first place come to love

him did not give up their affection for him.

On the third day he appeared to

them restored to life, for the prophets of God had prophesied these and

countless other marvellous things about him. And the tribe of Christians, so called after

him, has still to this day not disappeared.[7] (Italics added)

The majority of

scholars see this passage as basically authentic,but touched up with later

Christian interpolations—in particular the three items I have italicized. But mythicists

are eager to find ways of claiming that Josephus said nothing at all about

Jesus. Their usual method of trying to achieve this is to claim Eusebius made up

the entire passage up in the fourth century and then pretended he found it in Josephus.

Hence our author’s eagerness to repeat Burckhardt’s accusation. But there’s a problem.

In the context Burckhardt

wasn’t accusing Eusebius of falsifying excerpts of historical texts, but of falsely

spinning the story of Constantine to make him out to be a greater hero of the

Christian faith than he ever really was.[8] And indeed that is something that most

historians would grant to a degree.

It is quite a

different matter to imply from Burckhardt’s words that Eusebius was a willing

party to the invention of passages out of thin air. There is good reason to suggest he would not

do that. This is seen, for example, in the

fact that the quotations we aren’t sure of in Eusebius, passages from otherwise

lost works, or disputed passages such as this one, can be tested against the

host of other passages where he quotes from ancient works that are still

available.[9] His essential faithfulness

to his sources is perhaps seen most clearly in cases where Eusebius preserves passages

whose content conspicuously contradicts the interpretation he derives from them.[10]

© Ronald V.

Huggins 2/22/2019

[1] The idea of the

two groups as opposite ends of the same mindset is suggested by Maurice Casey

in his comments on our author, who is a convert to Atheism from Christianity:

[Dan

Barker’s] book is important to this discussion for one reason only: it can be

taken to show the damaging effect of the fundamentalist mindset upon attempts

at critical enquiry, that it can result in a merely different kind of preaching,

which still takes notice only of its own traditions” Jesus: Evidence and Arguments of Mythicist Myths (London: T&T Clark/Bloomsbury,

2014), 14.

The term “fundamentalist” is notoriously

slippery, as Alvin Plantinga amusingly pointed out when he noted that “On the

most common contemporary academic use of the term, it is a term of abuse or

disapprobation, rather like ‘son of a bitch’, more exactly ‘sonavabitch’, or

perhaps still more exactly (at least according to those authorities who look to

the Old West as normative on matters of pronunciation) ‘sumbitch’. When the term

is used in this way, no definition of it is ordinarily given. (If you called

someone a sumbitch, would you feel obliged first to define the term?) (Warranted Christian Belief Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2000], 245). In using the term here, I am referring to a certain

intellectual rigidity, laziness, and intransigence that, when accompanied by an

overblown sense of self-confidence and certainty of one’s own views, ultimately

leads to a total contempt of and disregard for evidence. Such a mindset is by no means obviously connected

to one’s being theologically conservative or liberal, since examples of cases

of this mindset can readily be named from both camps. So in using the term I in

no way refer to the more nuanced perspectives reflected, for example, in J. I.

Packer’s “Fundamentalism” and the Word of

God (1958), in the more conservative side of the so-called Fundamentalist-Modernist

Controversy of the 1920s, represented by J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity

and Liberalism (1923), nor even in the range of views reflected in the originally

twelve-part and later four-volume collection published in the second decade of

the last century called The Fundamentals.

In each of these cases “Fundamentalism” primarily referred to an adherence to

the central tenets, or core beliefs of historic Christianity, the Regula Fidei, the endorsement of the historic

Creeds, Confessions and so on.

[2]David

W. Daniels, Babylon Religion: How a

Babylonian [G]oddess became the

Virgin Mary, (illustrated by Jack T. Chick; Ontario, CA. Chick Publications,

2006), 161.

[3] Dan Barker, Godless: How an Evangelical Preacher Became

One of America's Leading Atheists (fwd. Richard Dawkins; Berkeley, CA:

Ulysses Press, 2008), 255.

[4] http://www.tertullian.org/rpearse/eusebius/eusebius_the_liar.htm.

[5] Jacob Burckhardt,

The Age of Constantine (trans. Moses

Hadas; Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor, 956), 250.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Josephus, Antiquities 18.63.3

(ET: Louis H. Feldman, Josephus (volume 9 of 10; Loeb Classical Library;

Cambridge: Harvard University Press; London: Heinemann, 1965), 49 and 51.

[8] Burckhardt, Age of Constantine, 250.

[9]Sabrina Inowlocki, Eusebius and the Jewish Authors: His Citation

Techniques in an Apologetic Context (Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2006).

[10] For a measured survey of views on

and evaluation of Eusebius’s faithfulness in quotation, see Inowlocki, Eusebius and Jewish Authors, , 87-104.

Comments

Post a Comment